3.3 — Profit, Capital, & Interest

ECON 452 • History of Economic Thought • Fall 2022

Ryan Safner

Associate Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/thoughtF22

thoughtF22.classes.ryansafner.com

Classical Confusion: Profits & Interest

Recall: Classical writers conflated profits and interest

Divided up society in functional terms: land, labor, capital

- each earns a return: wages, rent, profits

Roles of capitalist and entrepreneur often were the same person, historically

In modern times, capitalist and entrepreneur often (but not always) different persons

The Problem of Profit

Marginal Productivity Theory: The Problem of Profit

John Bates Clark

1847—1938

J.B. Clark: is entrepreneurship a fourth factor of production that is paid its marginal product?

Entrepreneur qua manager of a firm does not earn profit, earns wage (for labor services of managing)

“Pure profit” must be a residual remaining after all factors of production (costs to firm) are paid

- on competitive market in long run equilibrium, all factors are paid their marginal products, equal to opportunity cost, \(p=MC\)

Real world profit exists, which must imply either:

- real world markets are not perfectly competitive

- real world markets are not in long run equilibrium

Marginal Productivity Theory: The Problem of Profit

John Bates Clark

1847—1938

Firms assume risks when they purchase factors of production in hopes of producing & selling output

- Must contractually pay the factors

- Must forecast consumers’ willingness to pay for the final product

If \(R(q)>C(q)\), then pure profits \(\pi>0\)

If \(R(q)<C(q)\), then losses \(\pi<0\)

Profits in competitive markets must \(\implies\) current disequilibrium as we are moving twaords long-run equilibrium (where \(\pi = 0 )\)

Frank Knight

Frank H. Knight

1885-1972

One of the key founders of the Chicago School of Economics

- Milton Friedman, George Stigler, Ronald Coase, James Buchanan all famous students/influenced by Knight

Marginalist who clarified the purpose of perfect competition model, profits, entrepreneurship

- Largely from an exploration of uncertainty

Famous 1921 dissertation from Cornell: Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit

Other work on public policy, competition, implications of increasing returns, etc

Profits and Uncertainty

Frank H. Knight

1885-1972

"Uncertainty must be taken in a sense radically distinct from the familiar notion of Risk, from which it has never been properly separated...The essential fact is that 'risk' means in some cases a quantity susceptible of measurement, while at other times it is something distinctly not of this character; and there are far-reaching and crucial differences in the bearings of the phenomena depending on which of the two is really present and operating...It will appear that a measurable uncertainty, or 'risk' proper, as we shall use the term, is so far different from an unmeasurable one that it is not in effect an uncertainty at all," (p.21)

Knight, Frank H, 1921, Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit

Uncertainty \(\neq\) Risk

Uncertainty \(\neq\) Risk

"Known knowns": perfect information

"Known unknowns": risk

- We know the probability distribution of states that could happen

- We just don't know which state will be realized

- We can estimate probabilities, maximize expected value, minimize variance, etc.

Uncertainty \(\neq\) Risk

- "Unknown unknowns: uncertainty

- We don’t even know the probability distribution of states that could happen

- No model to optimize in a world of uncertainty!

Profits and Uncertainty

Frank H. Knight

1885-1972

“The primary attribute of competition...is the ‘tendency’ to eliminate profit or loss, and bring the value of economic goods to equality with their cost...Hence the problem of profit is one way of looking at the problem between perfect competition and actual competition...The key to the whole tangle will be found to lie in the notion of risk or uncertainty and the ambiguities concealed therein,” (pp.18-19).

Knight, Frank H, 1921, Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit

Profits and Uncertainty

Frank H. Knight

1885-1972

“It is this ‘true’ uncertainty, and not risk, as has been argued, which forms the basis of a valid theory of profit and accounts for the divergence between actual and theoretical competition,” (pp.18-19).

“The prime essential to that perfect competition which would secure in fact those results to which actual competition only ‘tends,’ is the absence of Uncertainty (in the true, unmeasurable sense)...[Risk] does not preclude perfect planning [and] cannot prevent the complete realization of the tendencies of competitive forces, or give rise to profit,” (pp.20-21)

Knight, Frank H, 1921, Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit

The Role of Entrepreneurial Judgment

Frank H. Knight

1885-1972

“Knightian uncertainty”: not that we can’t assign probabilities to each outcome; we do not even have the knowledge necessary to list all possible outcomes!

Requires entrepreneurial judgment to both:

- estimate possible actions and

- estimate the likelihood of their success

Entrepreneur is central player, earns pure profits (a residual, not a “marginal product”!) for bearing uncertainty

Langlois, Richard L. and Metin Cosgel, 1993, "Frank Knight on Risk, Uncertainty, and the Firm: A New Interpretation," Economic Inquiry 31

Entrepreneurial Judgment

Henry Ford

1863-1947

“If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” - Henry Ford

Entrepreneurial Judgment

“It's really hard to design products by focus groups. A lot of times, people don't know what they want until you show it to them.” - Steve Jobs

The Problem of Interest

The Problem of Interest

Remains controversial to this day

“Capital” is:

- hard to define or (especially) aggregate

- necessarily bound up with time and uncertainty

History of Interest Theories

Mercantilists believed interest rates determined by monetary factors (money supply)

- Cantillon: interest rates affected by real factors, but \(\uparrow\) money supply might \(\uparrow / \downarrow\) interest rates depending on who gets new money (savers or borrowers)

Classicals argued for real (non-monetary) causes

- Money is neutral, just a veil

- Hume disproved monetary theory of interest rates with his thought experiments

- interest determined by investment spending, productivity of capital

History of Interest Theories

Adam Smith

1723-1790

“What is annually saved is as regularly consumed as what is annually spent, and nearly in the same time too; but it is consumed by a different set of people. That portion of his revenue which a rich man annually spends, is in most cases consumed by idle guests, and menial servants, who leave nothing behind them in return for their consumption. That portion which he annually saves, as for the sake of the profit it is immediately employed as a capital, is consumed in the same manner, and nearly in the same time too, but by a different set of people, by labourers, manufacturers, and artificers, who re-produce with a profit the value of their annual consumption,” (Book II, Chapter 3).

History of Interest Theories

David Ricardo

1772-1823

“[The interest rate depends] on the rate of profits which can be made by the employment of capital, and which is totally independent of the quantity, or of the value of money. Whether a Bank lent one million [£], ten million, or a hundred million, they would not permanently alter the market rate of interest, they would alter only the value of the money they had this issued.”

Ricardo, David, 1817, Principles of Political Economy and Taxation

The Problem of Interest

John Bates Clark

1847—1938

Marginal productivity theory & product exhaustion created a problem:

- MPT explains all revenues from firm sales ultimately go to factors of production as income (costs to firm)

- Each factor paid its marginal product, contribution to production

So then what is this return on capital — interest — that seems more than is necessary to bring capital into use?

- Capital owner seems to get a perpetual flow of income as interest

The Problem of Interest

Capital is not an original factor, it is just land and labor combined in the past (i.e. someone had to make the shovel, the factory, etc. with land & labor)

Marginal product of capital should just be the value of the land and labor used to make the capital in the past

- But capital earns interest!

Capital makes land & labor more productive, maybe interest is that extra productivity?

- But: MPT implies that labor and land each are already paid more from their higher marginal products (due to having the capital)!

Interest even exists in long-run equilibrium of perfect competition (when profits disappear)

Böhm-Bawerk on Interest

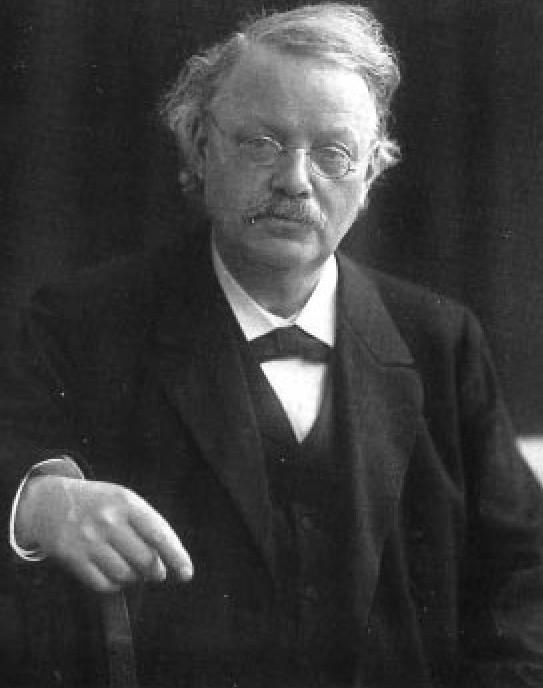

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk

1851—1914

Wrote to dispute Marxist exploitation theory (which condemns profit & interest as exploitation)

- fundamental misunderstanding of capital, profit, and interest

Writes against theories of interest based on:

- monetary factors

- exploitation (Marxism)

- productivity of capital

Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen von, 1896 Karl Marx and the Close of His System

Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen von, 1884, History and Critique of Interest Theories

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk: On The Origin of Interest

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk

1851—1914

- Source of interest is in the technological relationship between goods, independent of institutions

- Even in a socialist society there would be interest

“Present goods are, as a rule, worth more than future goods of a like kind a number. This proposition is the kernel and center of the interest theory which I have to present” (Positive Theory of Capital)

- Tried to explain why the exchange, the “agio” (ratio) between present & future goods is positive

- premium on present goods

- discount future goods

Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen von, 1884, History and Critique of Interest Theories

Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen von, 1888, The Positive Theory of Capital

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk: On The Origin of Interest

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk

1851—1914

- Famously gives three reasons for why present goods are valued higher than future goods

“Difference circumstances of want and provision in the present and future”

“We systemaically underestimate future wants, and the goods which are to satisfy them”

“More roundabout” methods of production are more productive than direct methods

- not all roundabout methods, i.e. not Rube-Goldberg machines

Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen von, 1884, History and Critique of Interest Theories

Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen von, 1888, The Positive Theory of Capital

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk: Roundaboutness

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk

1851—1914

Third reason generated the most controversy

“Roundaboutness” implies a longer production period

- Think about Menger’s (higher) orders of goods

- Define “capital” as “goods-in-process” (orchard trees growing), i.e. goods of higher order (than 1)

- Increasing capital inreases the length of the production process (reaches back into higher and higher orders)

Tried to argue that production processes with more capital are more productive, and that they have a longer “average period of production” due to roundaboutness

Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen von, 1888, The Positive Theory of Capital

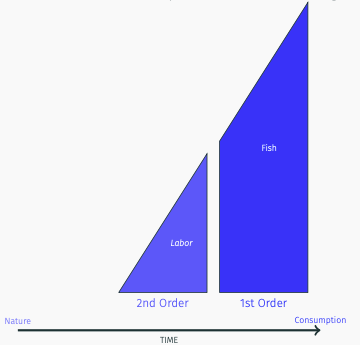

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk: Roundaboutness

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk

1851—1914

- Consider Robinson Crusoe fishing with his bare hands

Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen von, 1888, The Positive Theory of Capital

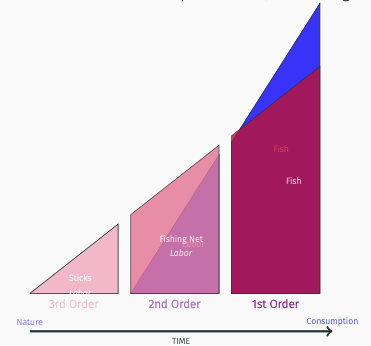

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk: Roundaboutness

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk

1851—1914

- Now suppose he invests in a net; by creating higher-order goods:

- increases the roundaboutness of production (goes through more orders, takes more time)

- increases the productivity of output

Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen von, 1888, The Positive Theory of Capital

Wicksell on Interest

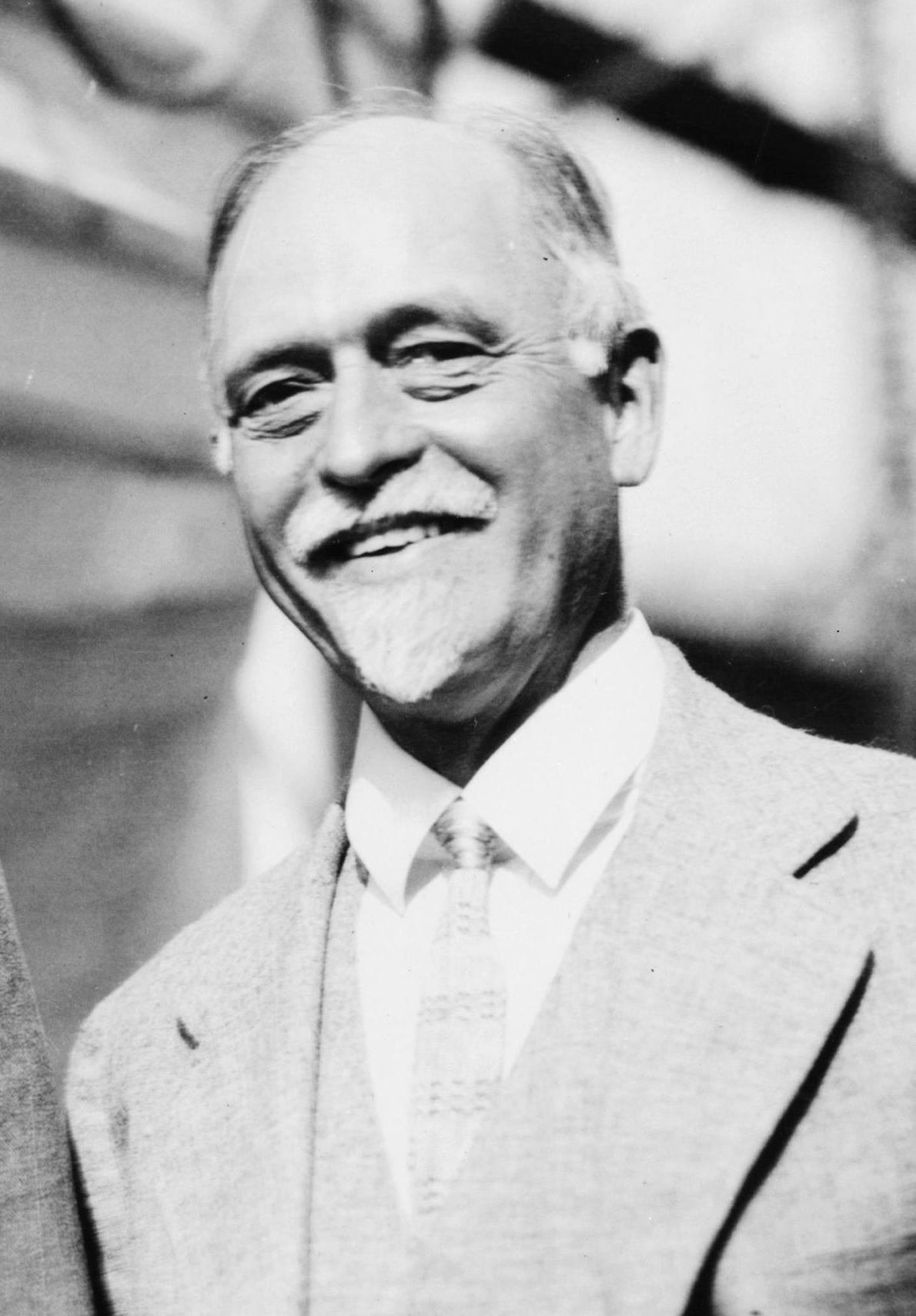

Knut Wicksell on Interest

Knut Wicksell

1851—1926

Praised and extended Böhm-Bawerk’s capital and interest theory

Disagreed with roundaboutness (B-B's third reason), thought that waiting was sufficient to explain interest rates

Knut Wicksell on Interest

Knut Wicksell

1851—1926

Distinguished between:

- “Natural rate of interest”: real rate of return on new capital

- vs. the “Market rate of interest”: rates quoted in market transactions

Saving = investment when market rate of interest \(\approx\) natural rate of interest

Wicksell, Knut, 1893, Über Wert, Kapital und Rente

Knut Wicksell’s Cumulative Process

Knut Wicksell

1851—1926

“Cumulative process”: if market interest rates fall below the natural rate (e.g. because of banks overissuing credit), demand for loanable capital increases, but savings supplied would fall

- investment would exceed savings (at lower rate), leads to “forced investment” and overinvestment

- this would increase spending, causing inflation

Takes quantity theory of money and turns it into a full theory of prices

Wicksell, Knut, 1893, Über Wert, Kapital und Rente

Knut Wicksell’s Cumulative Process

Knut Wicksell

1851—1926

- “Cumulative process”: conversely, if market interest rates rises above the natural rate, demand for loanable capital decreases, but savings supplied would rise

- savings would exceed investment (at higher rate), leads to “forced saving” and underinvestment

- this would decrease spending, causing deflation

Wicksell, Knut, 1893, Über Wert, Kapital und Rente

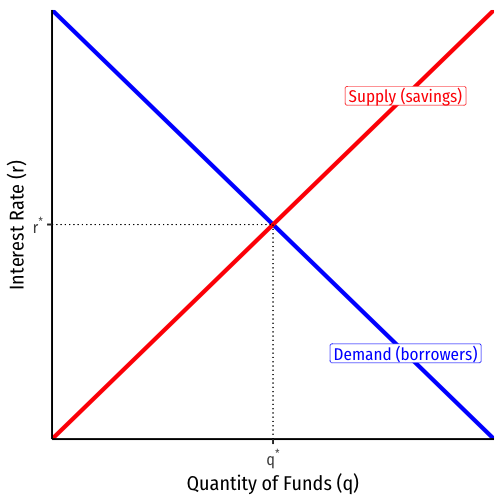

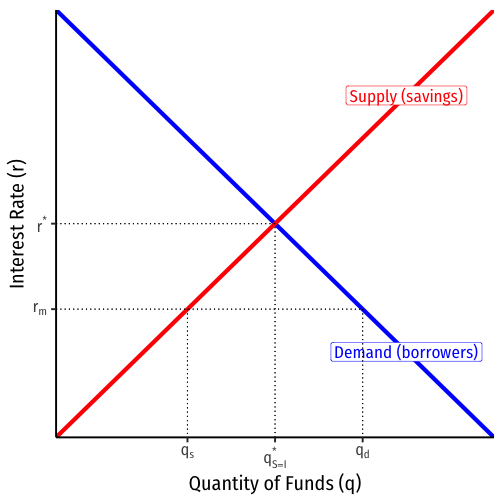

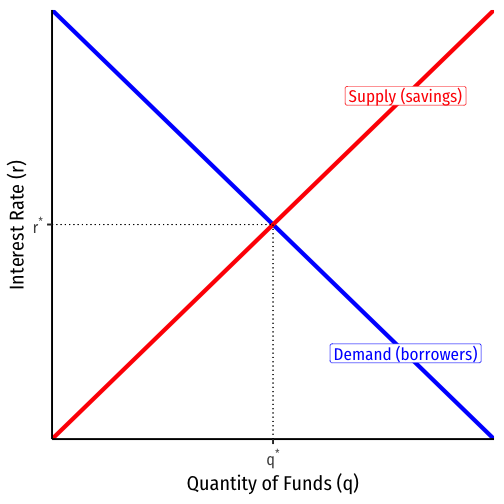

The Market for Loanable Funds

Consider the market for loanable funds

Upward-sloping Supply of savings

Downard-sloping Demand for loans (credit) for:

- investment — businesses looking for capital to build factories

- consumption — consumers looking for auto loans, mortgages, etc

Equilibrium “natural” rate of interest, \(r^\star\)

The Market for Loanable Funds: Cumulative Process

Suppose the market rate of interest \(r_m\) is below the natural rate \(r^\star\)

- likely caused by overissue of credit

Here, savings, \(\color{red}{q_s} < \color{blue}{q_d}\), investment

People will borrow and spend more than exists in real capital (savings)

- leads to higher spending, investment, and inflation (“boom”)

- may cause a boom and bust cycle, ending in depression (and deflation)

The Market for Loanable Funds: Cumulative Process

Knut Wicksell

1851—1926

Keeps quantity theory of money — in long run, money is neutral \((\uparrow M \implies \uparrow P)\)

But shows in short run, money is not neutral, changes in money can have changes in the real economy

Wicksell, Knut, 1893, Über Wert, Kapital und Rente

Irving Fisher on Interest

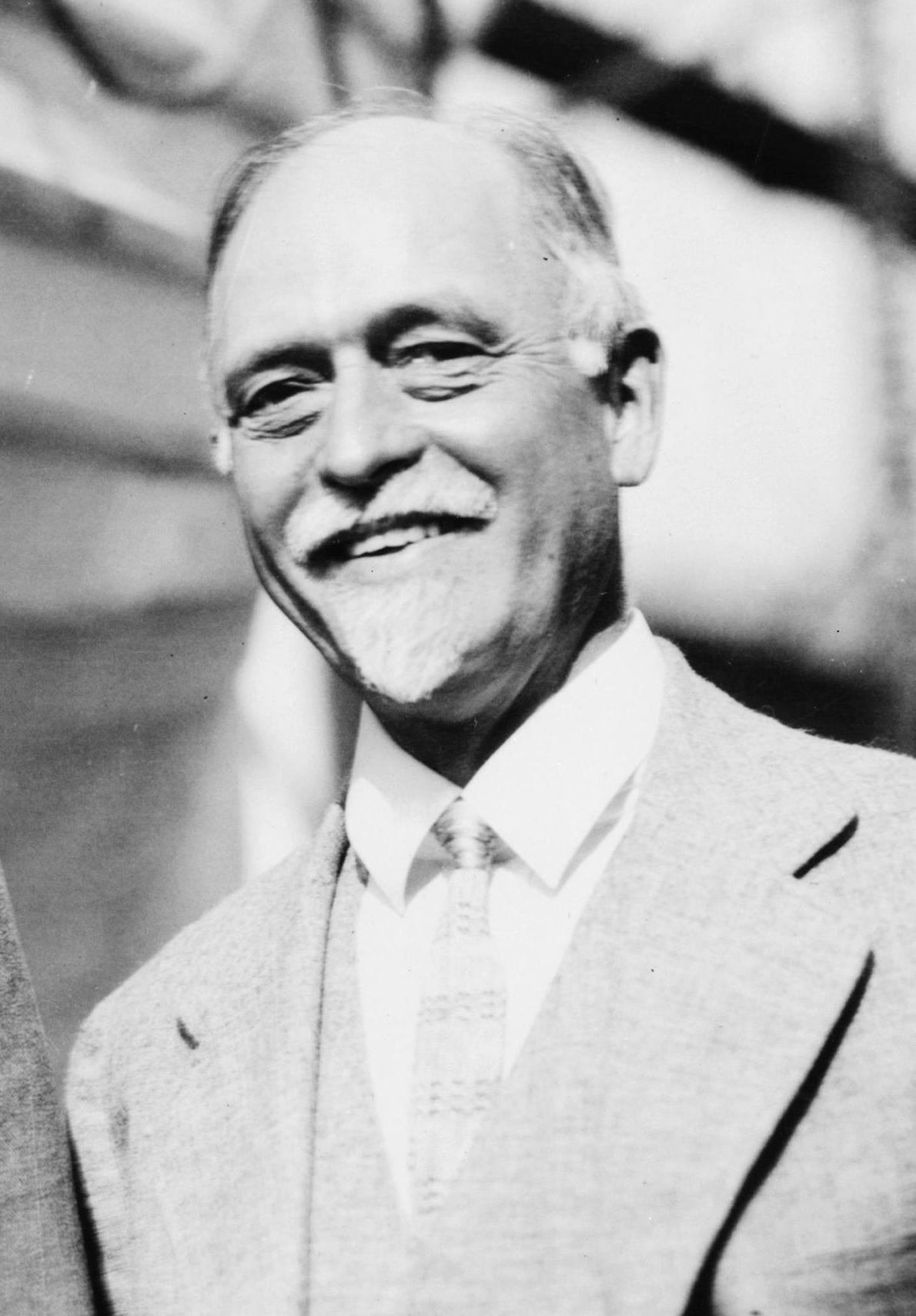

Irving Fisher

Irving Fisher

1867—1947

One of the greatest American economists in the first half of 20th century

Pioneer in capital & interest theory, quantity theory of money, debt-deflation theory of depression

Inventor of the predecessor to Rolodex — earned a fortune

A social reformer, a major Prohibitionist, teetotaler

Probably the first “celebrity economist”

- famously blew it in 1929, prognosticating that the “stock market has reached a permanently high plateau”

1907 The Rate of Interest, updated in 1930

Fisher: Quantity Theory of Money

Irving Fisher

1867—1947

“Equation of Exchange”: \(MV=PT\)

- \(M\) is stock of money

- \(V\) is velocity of circulation

- \(P\) is price level

- \(T\) is index of transactions

An accounting identity

Developed theory of index numbers to measure \(P\)

Fisher, Irving, 1911, The Purchasing Power of Money

Fisher: Quantity Theory of Money

Irving Fisher

1867—1947

“Equation of Exchange”: \(MV=PT\)

Exogenous \(\Delta M \implies\) endogenous \(\Delta P\) to equilibrate

Two key results of quantity theory of money

- Money is neutral in the long run (no permanent change in \(V\) or \(Y)\) from \(\Delta M\)

- Price level is directly proportional to money stock \((P \propto M)\)

Fisher: The Fisher Equation

Irving Fisher

1867—1947

Fisher hypothesis (or Fisher effect): real interest rate is independent of monetary factors (like nominal interest rate and expected inflation rate)

- nominal interest rate changes to follow the inflation rate

- monetary policy (e.g. new money) has no effect on real economy, money is neutral

Fisher equation: \(r \approx i - \pi^{e}\)

- \(r\): real interest rate

- \(i\): nominal interest rate

- \(\pi^e\): expected inflation rate

Irving Fisher on Capital & Interest

Irving Fisher

1867—1947

Thought Bohm-Bawerk's 3rd reason wouldn't exist without first two

- For psychological reasons (first 2), individuals have a time-preference for present over future goods

Discarded some incorrect parts of Bohm-Bawerk & essentially gave us our modern understanding of interest

B-B had followed classical distinction: land, labor, capital

- needed special theory to explain interest as return to capital, different from rent & wages

Fisher objected to the sharp distinciton between wages, rent, interest

- interest \(\neq\) share of income going to capital

Irving Fisher on Capital & Interest

Irving Fisher

1867—1947

- Examined flow of income to all individuals (as factor owners) over time

- The price of a durable good is the “capitalized value” of an income flow, discounted by current interest rate

- Interest return on a resource \(\implies\) comparing capitalized value with income flow over time

“The value of the future apples determines the capital value of the orchard.”

Irving Fisher on Capital & Interest

Irving Fisher

1867—1947

- Example: “Rent” on land — compare the future flow of rental income with capitalized value (price) of land, the return is interest

- Price of land capitalizes the future-discounted flow of future services (income)

“Rent and interest are merely two ways of measuring the same income,” (p.331)

- Same with labor income: obtaining higher skills will increase your future income flow, you are investing in your human capital

- must decide if the cost is worth it, by comparing future-discounted expected income stream with vs. without skills

“Interest is not a part, but the whole, of income.” (p.332)

Irving Fisher on Capital & Interest

Irving Fisher

1867—1947

“The value of the orchard depends upon the value of its crops: and in this dependence lurks implicitly the rate of interest itself.”

- Interest rate is a price of future goods in terms of present goods

- How much individuals will pay to receive income now vs. later

“the (percentage) excess of the present marginal want for one more unit of present goods over the present marginal want for one more unit of future goods”

- Investment in capital: present consumption can be saved to buy/build machinery that can increase future income flows

Present vs. Future Goods

What are future goods?

Futures: claims on goods to be delivered at a future date

- corn futures, oil futures, etc.

Financial assets: bonds, lottery winnings, IOUs

Real goods: immature orchard of fruit trees; durable goods that yield output later

Present vs. Future Goods

Consider goods-bundles consumed now vs. consumed at later date

- i.e. not apples vs. oranges, but apples and oranges today vs. apples and oranges next year

Agent's objective: optimize time-profile of consumption, maximize net present value

Fisher calls goods-bundles “income’ but he really just means consumption

Present vs. Future Goods

- Time Value of Money: same nominal amount of money† is worth different amounts over time

$$\begin{align*} PV &= \frac{FV}{(1+r)^n}\\ FV &= PV(1+r)^n\\ \end{align*}$$

- \(PV\): present value

- \(FV\): future value

- \(r\): interest rate

- \(n\): number of time periods

† Or income, or consumption...

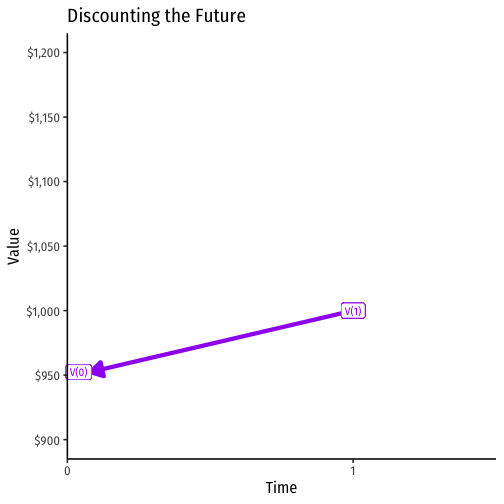

Present vs. Future Goods

- Example: what is the present value of getting $1,000 one year from now at 5% interest?

$$\begin{align*} PV &= \frac{FV}{(1+r)^n}\\ PV &= \frac{1000}{(1+0.05)^1}\\ PV &= \frac{1000}{1.05}\\ PV &= \$952.38\\ \end{align*}$$

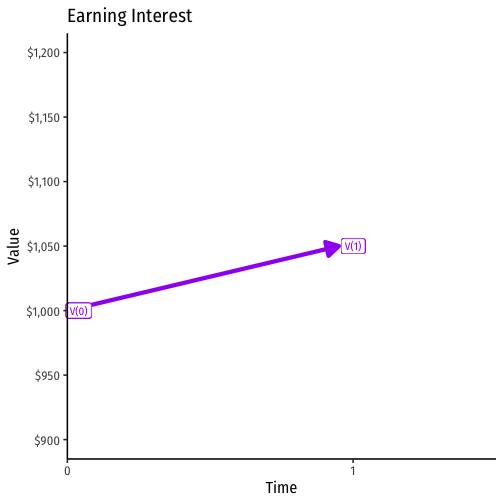

Present vs. Future Goods

- Example: what is the future value of $1,000 lent for one year at 5% interest?

$$\begin{align*} FV &= PV(1+r)^n\\ FV &= 1000(1+0.05)^1\\ FV &= 1000(1.05)\\ FV &= \$1050\\ \end{align*}$$

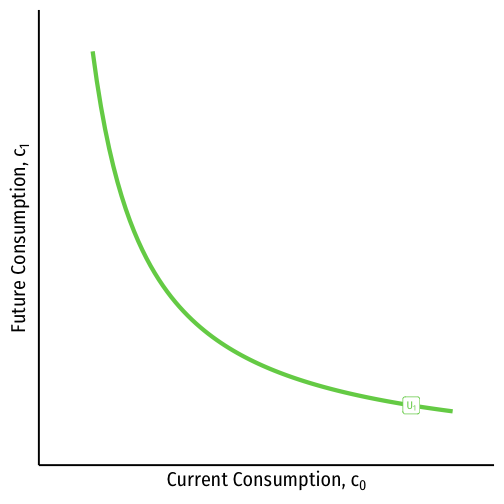

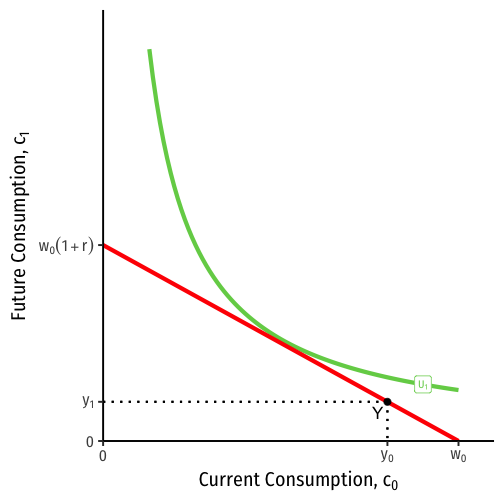

Time Preference: Present vs. Future Goods

Individuals have a time preference (“impatience”), a subjective ranking over bundles of consumption \((c_0,c_1)\):†

- \(c_0\): current consumption (period \(t=0)\)

- \(c_1\): future consumption (period \(t=1)\)†

Represent as an indifference curve‡

Marginal Rate of (Intertemporal) Substitution: rate at which person gives up future goods \((c_1)\) for 1 more present good \((c_0)\) (i.e. slope)

† Or we could consider a perpetual flow of income, \(c\)..

‡ Indifference curves, BTW, are invented by Edgeworth around this time

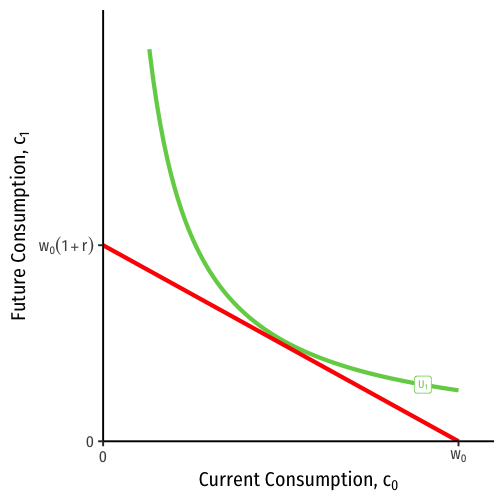

Time Preference: Present vs. Future Goods

Individual has current wealth \(w_0\)

Opportunities for market exchange in credit markets

- exchange present goods for claims on future goods with interest rate \(r\)

- will enjoy future consumption \((1+r)\) times however much is saved & lent

Time Preference: Present vs. Future Goods

For convenience, assume a “numeraire”: set price of current consumption \(p_{c_0}=1\)

Conventionally, price of future goods in terms of present goods is \(\frac{1}{(1+r)}\)

Slope of market exchange line is ratio of prices: \(-\frac{\Delta c_1}{\Delta c_0}=-\frac{p_{c_0}}{p_{c_1}}\); with \(p_{c_0}=1\), slope is \(-(1+r)\)

Time Preference: Present vs. Future Goods

Intertemporal “opportunity cost”: 1 unit of present goods buys \((1+r)\) units of future goods; must give up \((1+r)\) units of future goods to get 1 unit of present good

- Future goods are discounted by \(\frac{1}{(1+r)}\), also called the “discount rate” \((\delta)\)

Higher interest rate \(r \implies\) steeper line, higher cost of present consumption relative to future consumption

\(r>0\), and slope is negative because it’s a price

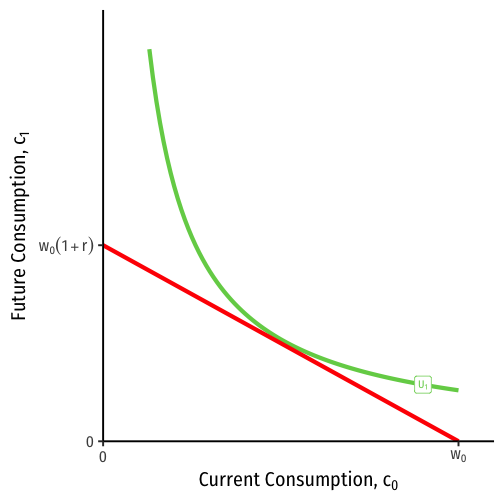

Time Preference: Present vs. Future Goods

- Individual starts with some endowment bundle, Y: \((y_0,y_1)\)

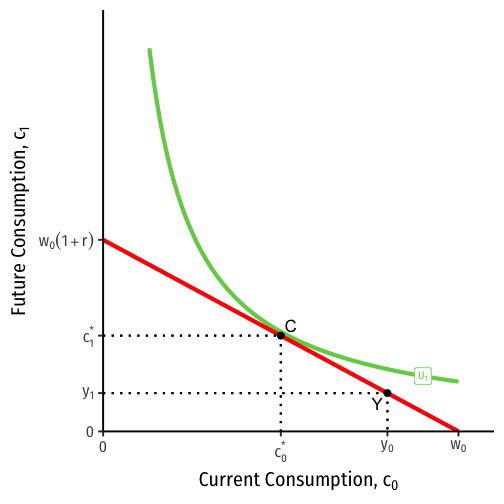

Time Preference: Present vs. Future Goods

Individual starts with some endowment bundle, Y: \((y_0,y_1)\)

“Excess demand” amount consumer wishes to consume (for \(c_0\) or \(c_1)\) relative to their endowment

- Positive or negative, depending on time preference and interest rate

- Negative excess demand for \(c_0 \implies\) will save & lend present goods

- Positive excess demand for \(c_1 \implies\) will consume more in future

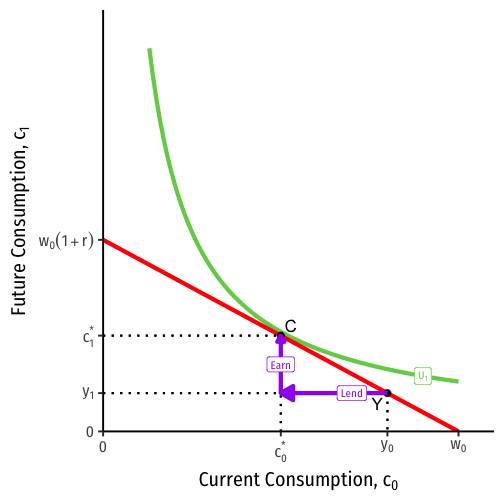

Time Preference: Present vs. Future Goods

This individual will trade away (save & lend) \((y_0-c^*_0)\) of \(c_0\) to earn \((c^*_1-y_1)\) of \(c_1\)

To reach consumption optimum C: \((y_0^*,y_1^*)\) $$\underbrace{\frac{MU_{c_0}}{MU_{c_1}}}_{MRIS}=\frac{p_{c_0}}{p_{c_1}}$$

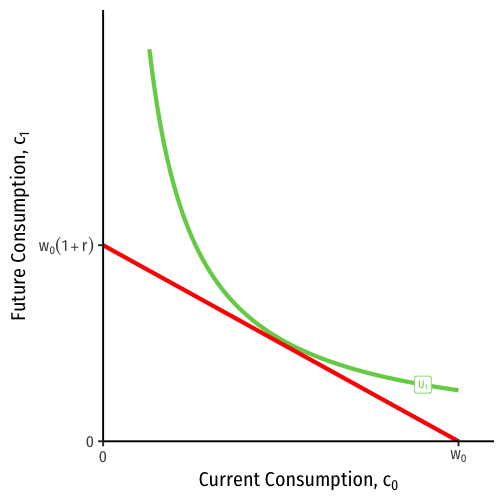

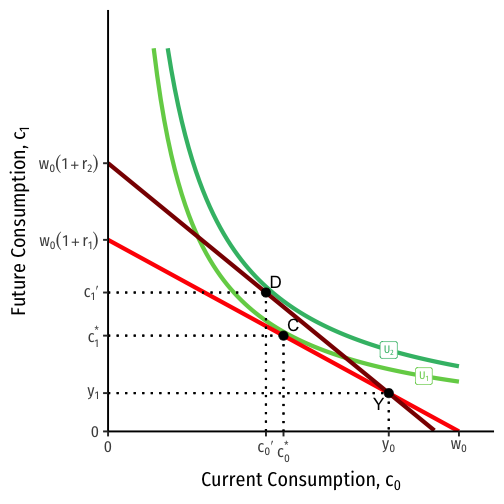

Time Preference: Present vs. Future Goods

If the market interest rate changes from \(r_1 \rightarrow r_2\), will change consumption optima to D†

Higher interest rate \(r \implies\) steeper line, higher cost of present consumption relative to future

Increase in the interest rate \((r_1 \rightarrow r_2)\)

- Consume less today \(y_0 \rightarrow c_0'\)

- Earn more in future \(y_1 \rightarrow c_1'\)

Decrease in the interest rate \((r_1 \leftarrow r_2)\)

- Consume more today \(y_0 \rightarrow c_0*\)

- Earn less in future \(y_1 \rightarrow c_1*\)

† Assuming income effects are dominated by substitution effects!

Time Preference: Present vs. Future Goods

- Market interest rate determined by summing up all individual:

- Excess demand for \(c_0\) (want to borrow for more present consumption)

- Excess demand for \(c_1\) (willing to lend savings)

Some Takeaways (Non-Technical)

Interest rate theory is relative price theory!

Interest rate is just another relative price, the price of future goods in terms of present goods

(Real) interest rate reflects time preferences of society (a real factor, money only influences the nominal interest rate)

A flow of future income (or services) can be described by its price, or capitalized value

Interest rates have important effects on investment, capital, and may play a role in business cycles