4.1 — Historical & Institutional Schools

ECON 452 • History of Economic Thought • Fall 2022

Ryan Safner

Associate Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/thoughtF22

thoughtF22.classes.ryansafner.com

Heterodox Economics

We've focused solidly on “orthodox economics”

- British Classicals through marginalism

- A clear trajectory to modern economic theory (but they’re not identical!)

Today we look at some famous heterodox writers gaining traction at the same time as the marginalist revolution (mid—late 19th century in to early 20th century)

Critical of “neoclassical” economics (Classical & marginalist synthesis)

- Critical of methodology and scope

- Critical of worldview and ideology

Heterodox Economics

Two (broad) heterodox schools of thought during two key eras:

German Historical School in central Europe

- “Older” school in 1840s-1870s

- “Younger” school in 1870s-1900

- Famous “Methodenstreit” with Menger & Austrians in 1880s

- Fades away by 1930s

Institutionalists in United States (1890s-1930s)

- Fades away by 1930s

- New Institutional Economics (1970s-Present)

The German Historical School

The German Historical School

English Classical (and marginalist) economics did not penetrate much into central Europe

Diverse group of writers throughout 19th century in German-speaking states

- “Germany” not united until 1871

Broadly speaking: generally placed more stock in concrete historical analysis, skeptical of “universal” principles or abstract models

The German Historical School

Several waves of Historicism:

“Older School”: Wilhelm Roscher, Karl Knies, Bruno Hildebrand (c.1840s—c.1870s)

- anticipated by Friedrich List

- theories of “stages of development” of countries

“Younger School” dominated by Gustav von Schmoller (c.1870s—1900s)

- rejection of universal laws of economics & deductive method

- inductive and comparative, focused on time and location

- focus on State-led policy & reforms

Predecessor: Friedrich List

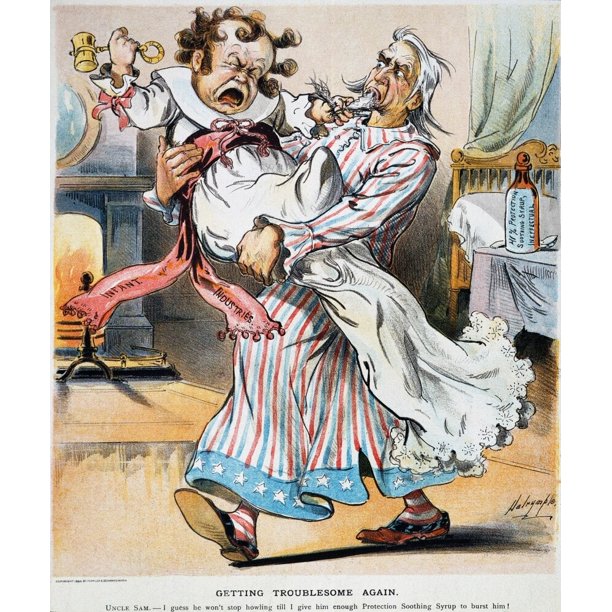

Friedrich List

1789—1846

Born in Germany, got in trouble and fled to the United States

Impressed by the American system protecting infant industries in America

Became perhaps the most famous protectionist

1841 The National System of Political Economy

- Became the Bible of protectionists, as the Wealth of Nations was to free traders

Later returned to Germany, helped create the Zollverein and push for unification

Friedrich List

Friedrich List

1789—1846

Criticized Adam Smith for being too cosmopolitan, putting the interests of the world first, not the interests of the nation

- Though Smith did argue free trade would benefit Britain (as well as the world)

Rejected Classical economic theory, focused more on historical study

List was concerned with national economic power, not just the increase of wealth and prosperity

“The power of producing wealth is...infinitely more important than wealth itself!”

List, Friedrich, 1841, The National System of Political Economy

Friedrich List: Importance of National Orientation

Friedrich List

1789—1846

“[A] nation would act unwisely to endeavour to promote the welfare of the whole human race at the expense of its particular strength, welfare, and independence. It is a dictate of the law of self-preservation to make its particular advancement in power and strength the first principles of its policy”

List, Friedrich, 1841, The National System of Political Economy

Friedrich List: On Production

Friedrich List

1789—1846

Thinks Classicals focused too much on consumption, government should focus on production

- “[P]roduction renders consumption possible.”

Largely endorsed mercantilist policies, privileging manufacturing

“It may be stated as a principle that a nation is richer and more powerful, in proportion as it exports more manufactured products, imports more raw materials, and consumes more tropical commodities.”

List, Friedrich, 1841, The National System of Political Economy

Friedrich List: Regulations Must be Targeted

Friedrich List

1789—1846

“It is bad policy to regulate everything and to promote everything by employing social powers, where things may better regulate themselves and can be better promoted by private exertions; but it is no less bad policy to let those things alone which can only be promoted by interfering social power.”

Friedrich List: On Protecting Manufacturing

Friedrich List

1789—1846

- This only works for specific circumstances:

“The system of protection can be justified solely and only for the purpose of the industrial development of the nation...Measures of protection are justifiable only for the purpose of furthering and protecting the internal manufacturing power, and only in the case of nations which through an extensive and compact territory, large population, possession of natural resources, far advanced agriculture, a high degree of civilization and political development, are qualified to maintain an equal rank with the principal agricultural manufacturing commercial nations.”

Friedrich List: On Protecting Manufacturing

Friedrich List

1789—1846

List is always in favor of free trade in everything except manufactured goods

Only thinks that large, powerful, temperate, advanced countries can extend their development by protecting manufacturing and industrializing

Largely from his study of Britain and the United States as leading examples

Sees the progress of great nations as a sequence from free trade to protectionism (for manufacturing), and then back to free trade

Friedrich List: On Protecting Manufacturing

Friedrich List

1789—1846

“History teaches us how nations which have been endowed by Nature with all resources which are requisite for the attainment of the highest grade of wealth and power, may and must...modify their [commercial] systems according to the measure of their own progress: in the first stage, adopting free trade with more advanced nations as a means of raising themselves from a state of barbarism, and of making advances in agriculture; in the second stage, promoting the growth of manufactures, fisheries, navigation, and foreign trade by means of commercial restrictions; and in the last stage, after reaching the highest degree of wealth and power, by gradually reverting to the principle of free trade and of unrestricted competition in the home as well as in foreign markets.”

Following English Practice, Not Classical Theory

Friedrich List

1789—1846

Classicals can preach all they want about Free Trade in the abstract, but actual British policy was still largely protectionist

This protection is what made England wealthy

“Had the English left everything to itself—'Laissez faire, laissez aller', as the popular economical school recommends—the [German] merchants of the Steelyard would be still carrying on their trade in London, the Belgians would be still manufacturing cloth for the English, England would have still continued to be the sheep-farm of the Hansards, just as Portugal became the vineyard of England, and has remained so till our days, owing to the stratagem of a cunning diplomatist. Indeed, it is more than probable that without her [highly protectionist] commercial policy England would never have attained to such a large measure of municipal and individual freedom as she now possesses, for such freedom is the daughter of industry and wealth.”

Friedrich List: Free Trade is the Eventual Goal

Friedrich List

1789—1846

“The system of protection, inasmuch as it forms the only means of placing those nations which are far behind [dominant England]...the system of protection regarded from this point of view appears to be the most efficient means of furthering the final union of nations, and hence also of promoting true freedom of trade...In order to allow freedom of trade to operate naturally, the less advanced nations must first be raised by artificial means to that stage of cultivation to which the English nation has been artifically elevated.”

The Infant Industries Argument

List is only perhaps the most popular historical figure making what economists call the “infant industries argument”

Promote import substitution: specific key industries should receive special protection (via tariffs, quotas, subsidies etc.) that discourage competition (from more efficient foreign imports)

Eventually, once the industry matures (is no longer in the “infant” stage), it can stand on its own and compete with the rest of the world, protection can be lifted

Schmoller and the Younger Historical School

Gustav von Schmoller

1838-1917

Dominated all central European academic social science in late 19th century

- One could not obtain a professorship without Schmoller’s approval!

Called Kathedersozialist (Socialist of the chair)

- focused on State-led policy changes

- “The intellectual bodyguard of the house of Hohenzollern”

Schmoller and the Younger Historical School

Proclamation of the German Empire in the Hall of Mirrors of Versailles (1871)

The Methodenstreit

Methodenstreit (strife over methods) between Gustav von Schmoller & Carl Menger

- Menger: universal economic laws exist

- Schmoller: they don’t

Schmoller derides Menger & his followers as “The Austrians”

Debate mostly a distraction, but forces Menger & followers to focus on methodology

- Focus both on theory and empirics

Menger, Carl, 1883 Untersuchungen über die Methode der Socialwissenschaften und der politischen Oekonomie insbesondere (Investigations into the Method of the Social Sciences with Special Reference to Economics)

American Institutionalism

American Institutionalism

American economists were also skeptical of British classical (and marginalist) economics

Americans getting Ph.Ds from Germany (Historical school)

- e.g. Clark was a student of Karl Knies

Developed their (broadly speaking) approach: institutionalism

- critical of abstract models & assumptions about human behavior (i.e. rational-maximizers & equilibrium)

- focus on the role and evolution of social institutions, and how they affect humanity

Largely inspired by Thorstein Veblen

- Others: John R. Commons, Wesley C. Mitchell

- Much later: New Institutional Economics (1970s-Present)

Connected with Progressive Era ideas

Some Context: Progressive Era I

Frederick Winslow Taylor

1856-1915

Progressive Era (1890-1920), rise of Big Business

Taylorism and Efficiency Movement: industrial efficiency by methods of scientific management

- Apply scientific tools to study optimal production techniques, standardization, eliminate waste

Workers as cogs in a well-oiled machine

Some Context: Progressive Era II

Theodore Roosevelt

1858-1919

Progressive Era (1890-1920), rise of Big Business

Activism aimed at rationalizing society, economy

Activist government fine-tuning markets: antitrust, minimum wage, externalities

The Progressive Era (c.1890-c.1920)

The Progressive Era (c.1890-c.1920)

The Progressive Era (c.1890-c.1920): Big Business

L: Adolf Berle(1895-1971)

R: Gardiner Means (1896-1988)

“We now have single corporate enterprises employing hundreds of thousands of workers, having hundreds of thousands of stockholders, using billions of dollars' worth of the instruments of production, serving millions of customers, and controlled by a single management group. These are great collectives of enterprise, and a system composed of them might well be called 'collective capitalism,”

- Separation of ownership (shareholders) and control (management) in corporations

Berle, Adolf and Gardiner Means, 1932, The Modern Corporation and Private Propertt

The Progressive Era (c.1890-c.1920)

- Economic legislation to “rationalize” and regulate market economy

- Antitrust laws

- Labor laws: unions, child labor laws, minimum wages, health and safety

- Monetary changes: Federal Reserve, creation of income tax (13th Amendment)

The Progressive Era (c.1890-c.1920)

- Social legislation to enhance democracy:

- Women's suffrage (19th Amendment)

- direct election of Senators (17th Amendment)

- Primaries in party politics (to end political machines)

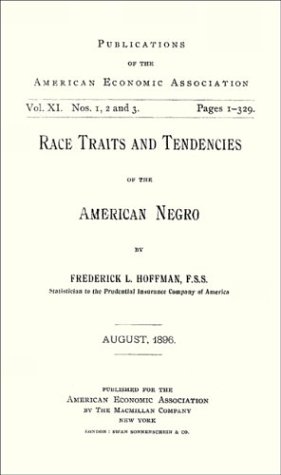

The Progressive Era (c.1890-c.1920): Eugenics

- But at same time, focus on scientific expert control of society

- Eugenics, scientific racism, forced sterilization of "imbeciles"

- Prohibition of alcohol (18th Amendment)

The Progressive Era (c.1890-c.1920): Eugenics

- But at same time, focus on scientific expert control of society

- Eugenics, scientific racism, forced sterilization of "imbeciles"

- Prohibition of alcohol (18th Amendment)

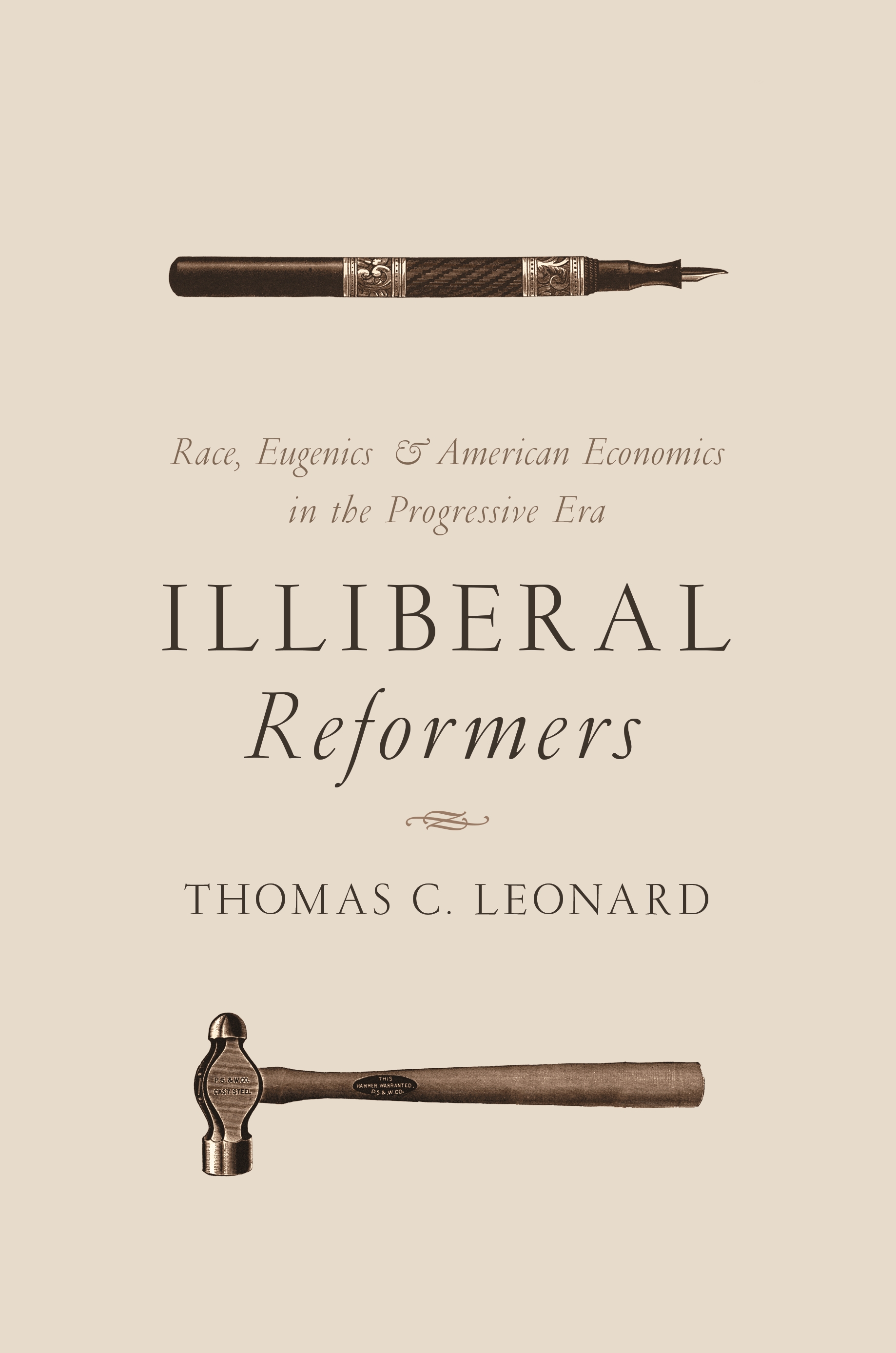

The Progressive Era (c.1890-c.1920): Eugenics

“Less well known is that a crude eugenic sorting of groups into deserving and undeserving classes crucially informed the labor and immigration reform that is the hallmark of the Progressive Era..Reform-minded economists of the Progressive Era defended exclusionary labor and immigration legislation on grounds that the labor force should be rid of unfit workers, whom they labeled “parasites,” “the unemployable,” “low-wage races” and the “industrial residuum.” Removing the unfit, went the argument, would uplift superior, deserving workers,” (pp.207-208)

Leonard, Thomas, 2005, “Retrospectives: Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 19(4):207–224

The Progressive Era (c.1890-c.1920): Eugenics

“Sidney and Beatrice Webb (1897 [1920], p. 785) put it plainly: ‘With regard to certain sections of the population [the “unemployable”], this unemployment is not a mark of social disease, but actually of social health.’ ‘[O]f all ways of dealing with these unfortunate parasites,’ Sidney Webb (1912, p. 992) opined in the Journal of Political Economy, ‘the most ruinous to the community is to allow them to unrestrainedly compete as wage earners,’” (p.213)

“Seager (1913a, p. 9) wrote: ‘The operation of the minimum wage requirement would merely extend the definition of defectives to embrace all individuals, who even after having received special training, remain incapable of adequate self-support.’” (p.213).

Leonard, Thomas, 2005, “Retrospectives: Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 19(4):207–224

The Progressive Era (c.1890-c.1920)

New independent agencies

- Interstate Commerce Commission (1887) to regulate railroads, trucking, telegraph & telephones

- Federal Trade Commission (1914) for antitrust, consumer protection

Science of public administration: substitution of democracy and markets with rule by technocratic experts insulated from politics and public opinion

Some Context: Progressive Era II

Woodrow Wilson

1856-1924

"The field of [public] administration is a field of business. [It] lies outside the proper sphere of politics...Although politics sets the tasks for administration, it should not be suffered to manipulate its offices"

"[P]ublic attention must be easily directed, in each case of good or bad administration, to just the man deserving of praise or blame. There is no danger in power, if only it be not irresponsible. If it be divided, dealt out in share to many, it is obscured."

Wilson, Woodrow, 1887, "The Study of Administration," Political Science Quarterly

Thorstein Veblen

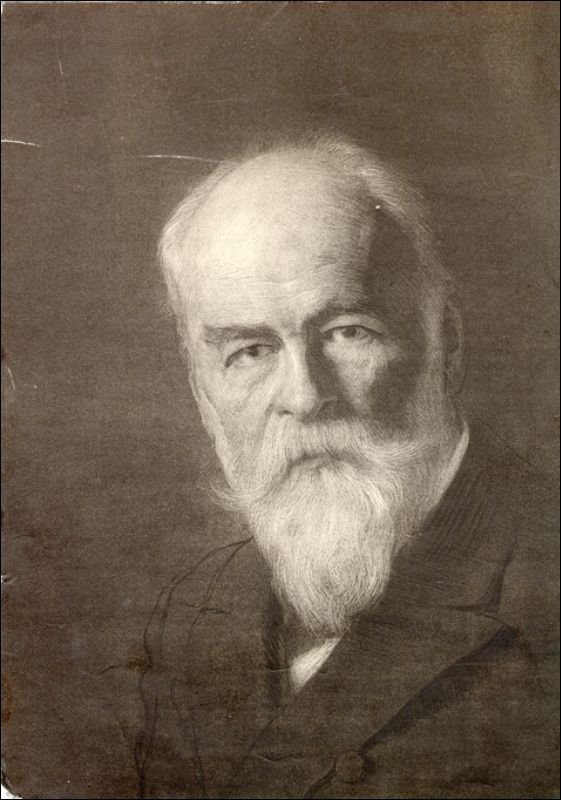

Thorstein Veblen

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

Highly influential critic of orthodox economics

A student of John Bates Clark (who himself was a student of German historicist Karl Knies)

Major founding influence of American institutionalism

Coined the term “neoclassical” economics — thought classical and new marginalist economics suffered from the same problems

Thorstein Veblen

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

Son of Norwegian immigrants to the Midwest (WI, MN)

Found it hard to assimilate into American mainstream economics profession

Obtained Ph.D in philosophy from Yale

Academic struggles, moving from college to college teaching

AEA eventually offered him presidency, but rejected it

“He was like a man from Mars observing the absurdities of the economic and social order with satirical wit” — Landreth & Colander (p.327)

Thorstein Veblen

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

Very idiosyncratic & penetrating writing style — people either love or hate it

Critique of both economic theory and the instititions of capitalism

- did not create an alternative system to rival

Focus on institutional analysis, motivated by Darwinian scientific approach

Thorstein Veblen on Neoclassical Economics

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

Critique of “neoclassical economics”

- contemporary orthodox economic theory (Marshall, Walras, etc) had classical roots

Veblen not interested in correcting flaws or extending previous theory (like Ricardo, Mill, Jevons, Marshall did); more interested in systematic critique striking at the root

Thorstein Veblen on Neoclassical Economics

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

Believed that neoclassical economics (and Marxian & Historical school for that matter) was unscientific

From Smith through Marshall, preconceived idea of social harmony via the Invisible Hand

- self-interest leads to social benefit

- before Smith, people believed that God ordered economy; seems to similar faith in Invisible Hand (Veblen was in/famously atheist)

- Marshal, Clark, etc. belief in competitive markets efficiency in long-run equilibrium

Veblen: equilibrium as used by orthodox theorists is an unproved normative claim (that it is good)

Thorstein Veblen on Neoclassical Economics

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

Veblen: orthodox theory is teleogical: oriented towards a clear end (long-run equilibrium)

- this is assumed in advance, and not empirically verified that it is attained (or desirable)

This is pre-Darwinian science!

- Darwin showed how evolution is non-teleological, a purely mechanical process without an end-goal

Thorstein Veblen on Neoclassical Economics

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

Veblen: a scientific approach to economics would be dynamic, Darwinian analysis of evolution of society (its institutions, culture, etc.)

Neoclassical economics is merely taxonomic: classifying parts of economy, but no theory of the evolution of institutions

- Focus on price theory assumes many things given & fixed (preferences, technology, institutions) to focus on prices & allocation of resources

- Veblen: we need to investigate the very things neoclassical theory holds constant, and explain how they change!

Thorstein Veblen on Neoclassical Economics

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

Veblen: producing goods & services, and earning profit (as a manager/capitalist) are two different things

- pursuit of profit comes from reduction of output, hurts society

Progressive Era view of Big Business: larger corporations aren’t aiming to improve efficiency, but to restrict output, raise prices, and profits to shareholders

- monopolization, trusts

- rise of anti-trust laws and regulations

Thorstein Veblen on Neoclassical Economics

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

- Veblen: neoclassical economics has ignored developments in biology, psychology, sociology, built a mechanistic model of human behavior

- the logic is correct, but the premises are wrong

“The psychological and athropological preconceptions of the economists have been those which were accepted by the psychological and social sciences some generations ago. The hedonistic conception of man is that of a lightning calculatior of pleasure and pains, who oscillates like a homogeneous globule of desire of happiness under the impulse of stimuli that shift him about the area, but leave him intact. He has neither antecedent nor consequent. He is an isolated, definitive human datum in stable equilibrium except for the buffets of the impinging forces that displace him in one direction or another.”

Veblen, Thorstein, 1919, “Why Is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science?” in The Place of Science in Modern Civilization

Thorstein Veblen on Culture

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

“The growth of culture is a cumulative sequence of habituation, and the way and means of it are the habitual response of human nature to exigencies that vary incontinently, cumulatively, but with something of a consistent sequence in the cumulative variations that so go forward—incontinently, because each new move creates a new situation which induces a further new variation in the habitual manner of response; cumulatively, because each new situation is a variation of what has gone before it and embodies as causal factors all that has been expected by what went before; consistently, because the underlying traits of human nature (propensities, aptitudes, and what not) by force of which the response takes place...remain substantially unchanged.”

Veblen, Thorstein, 1919, “The Limitations of Marginal Utility” in The Place of Science in Modern Civilization

Thorstein Veblen on Culture

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

“Not only is the individual’s conduct hedged about and directed by his habitual relations to his fellows in the group, but these relations, being of an institutional character, vary as the institutional scheme varies. The wants and desires, the end and aim, the ways and means, the amplitude and drift of the individual’s conduct are functions of an institutional variable that is of a highly complex and wholly unstable character.”

Veblen, Thorstein, 1919, “The Limitations of Marginal Utility” in The Place of Science in Modern Civilization

Thorstein Veblen on The Dichotomy

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

Individuals brought up in a culture act in accordance with established norms (which emerged from previous interactions)

“Instincts”: relatively-fixed constraints & motivations of human behavior

- parental, workmanship, curiosity, acquisitiveness instincts

- partially determined by culture

Instinctual drives create tensions

- i.e. self-interested acquisitiveness can harm society

- Economic analysis must address this basic tension

Thorstein Veblen on The Dichotomy

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

“Industrial/technological employments”: activities flowing from parenthood, workmanship, and curiosity

- Involve causal, factual, relationships

“Ceremonial behavior”: previously people explained these with religion or supernatural forces, but now science can explain them

- rooted in the past, an appeal to authority, cultural taboos, etc.

The more we advance science, the more we can explain without ceremonial behavior

This major dichotomy echoes throughout Veblen’s writings

Thorstein Veblen on The Dichotomy in Business

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

Ceremonial behavior in modern business: “pecuniary/business employments”

In pre-modern societies, workers owned own tools, produced via expression of workmaship instincts

- Income from these activities roughly measures effort exerted (Smithean labor theory of value)

In modern societies, workers and capitalists separate: acquisitiveness instinct dominates workmanship instinct

- Captains of industry, moneylenders, “get something for nothing”

Veblen, Thorstein, 1904, The Theory of Business Enterprise

Thorstein Veblen on Big Business

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

Big Business of early 20th century Progressive Era

Veblen thought they were not promoting the public good, but were amassing monopoly power

- “Advised idleness”: restrict output to raise prices & profits

- “Capitalization of inefficiency”

“Industry is carried on for the sake of business, but not conversely.”

Veblen, Thorstein, 1904, The Theory of Business Enterprise

Thorstein Veblen contra Marx

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

- Interestingly, criticizes Marxist approach to economics

“The claim that the system of competition has proved itself an engine for making the rich richer and the poor poorer has the fascination of epigram; but if its meaning is that the lot of the average, of the masses of humanity in civilized life, is worse to-day, as measured in the means of livelihood, than it was twenty, or fifty, or a hundred years ago, then it is farcical.”

Veblen, Thorstein, 1904, “Some Neglected Points in the Theory of Socialism,” in The Theory of Business Enterprise

Thorstein Veblen on The Leisure Class

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

Probably best known for Theory of the Leisure Class

Used dichotomy to discuss consumption

Ceremonial instincts lead people to revere wealth and power, in modern society ⟹ wealthiest captains of industry

- Must display their wealth in order to be recognized

- People emulate wealth-displaying activity: “conspicuous consumption” of fancy clothing, cars, houses, jewelry, private jets, etc.

Sometimes economists discuss “Veblen goods”: quantity demanded increases as price increases (i.e. upward-sloping demand)

Veblen, Thorstein, 1899, The Theory of The Leisure Class

Thorstein Veblen on Stability & Future of Capitalism

Thorstein Veblen

1857—1929

In general, Veblen saw ongoing struggle between industrial & pecuniary employments, and between ceremonial instincts vs. scientific/technological improvement

Rejected Marxist view that proletariat would become more miserable, and revolt to overthrow ruling class

- Though it may be that working classes may perceive to be relatively poorer than richest

- More about envy of relative wealth than about actual level of absolute wealth of poor

Future is uncertain, the only certainty is change & evolution

Veblen, Thorstein, 1899, The Theory of The Leisure Class